I’ve recently returned from the IEEE International Symposium on Field-Programmable Custom Computing Machines (known as FCCM). I used to attend FCCM regularly in the early 2000s, and while I have continued to publish there, I have not attended myself for some years. I tried a couple of years ago, but ended up isolated with COVID in Los Angeles. In contrast, I am pleased to report that the conference is in good health!

The conference kicked off on the the evening of the 4th May, with a panel discussion on the topic of “The Future of FCCMs Beyond Moore’s Law”, of which I was invited be be part, alongside industrial colleagues Chris Lavin and Madhura Purnaprajna from AMD, Martin Langhammer from Altera, and Mark Shand from Waymo. Many companies have tried and failed to produce lasting post-Moore alternatives to the FPGA and the microprocessor over the decades I’ve been in the field and some of these ideas and architectures (less commonly, associated compiler flows / design tools) have been very good. But, as Keynes said, “markets can remain irrational longer than you can remain solvent”. So instead of focusing on commercial realities, I tried to steer the panel discussion towards the genuinely fantastic opportunities our academic field has for a future in which power, performance and area innovation changes become a matter of intellectual advances in architecture and compiler technology rather than riding the wave of technology miniaturisation (itself, of course, the product of great advances by others).

We look older, and we don’t have beer.

The following day, the conference proper kicked off. Some highlights for me from other authors included the following papers aligned with my general interests:

- AutoNTT: Automatic Architecture Design and Exploration for Number Theoretic Transform Acceleration on FPGAs from Simon Fraser University, presented by Zhenman Fang.

- RealProbe: An Automated and Lightweight Performance Profiler for In-FPGA Execution of High-Level Synthesis Designs from Georgia Tech, presented by Jiho Kim from Callie Hao‘s group.

- High Throughput Matrix Transposition on HBM-Enabled FPGAs from the University of Southern California (Viktor Prasanna‘s group).

- ITERA-LLM: Boosting Sub-8-Bit Large Language Model Inference Through Iterative Tensor Decomposition from my colleague Christos Bouganis‘ group at Imperial College, presented by Keran Zheng.

- Guaranteed Yet Hard to Find: Uncovering FPGA Routing Convergence Paradox from Mirjana Stojilovic‘s group at EPFL – and winner of this year’s best paper prize!

In addition, my own group had two full papers at FCCM this year:

- Banked Memories for Soft SIMT Processors, joint work between Martin Langhammer (Altera) and me, where Martin has been able to augment his ultra-high-frequency soft-processor with various useful memory structures. This is probably the last paper of Martin’s PhD – he’s done great work in both developing a super-efficient soft-processor and in forcing the FPGA community to recognise that some published clock frequency results are really quite poor and that people should spend a lot longer thinking about the physical aspects of their designs if they want to get high performance.

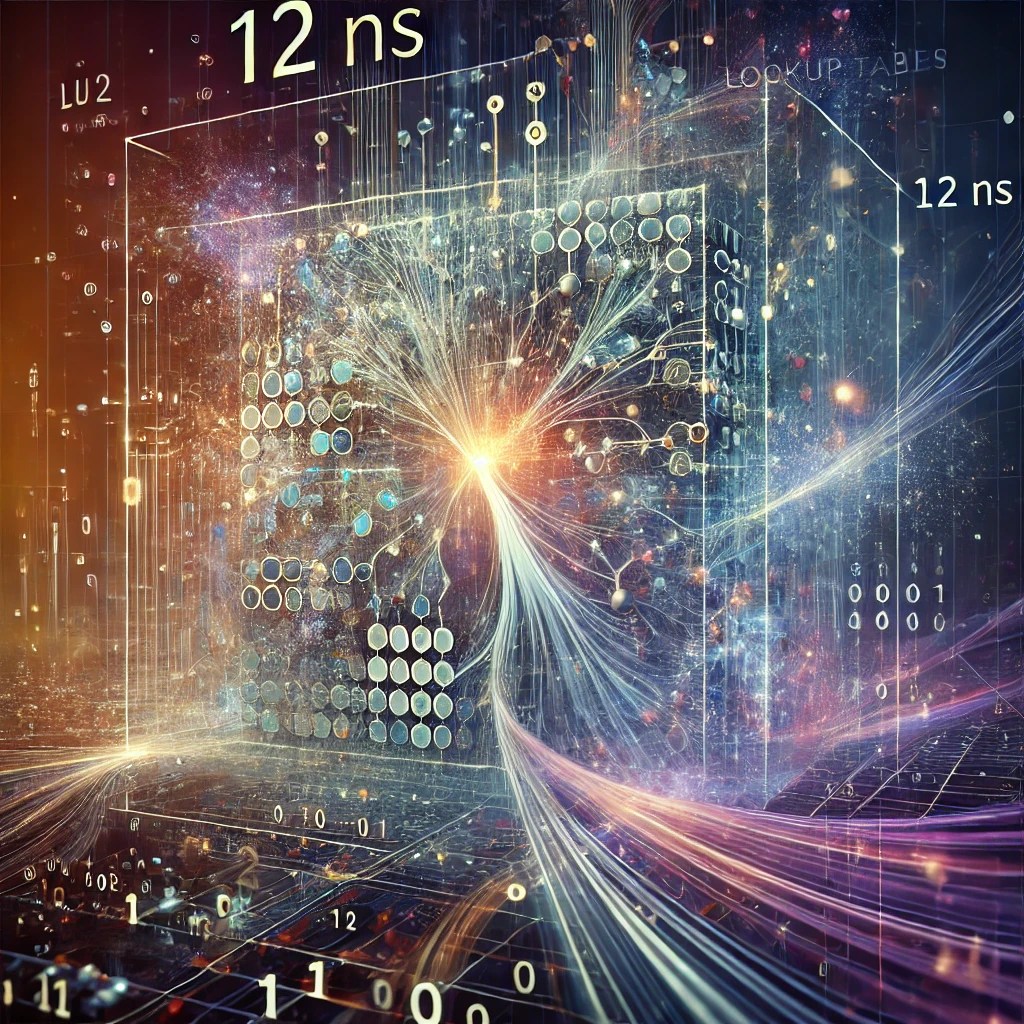

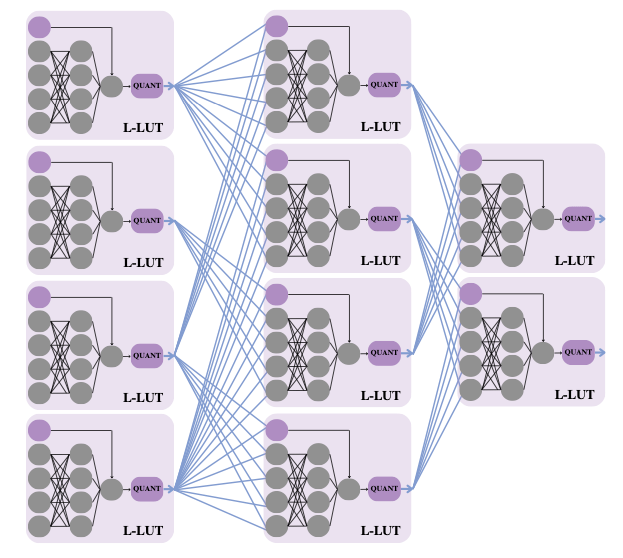

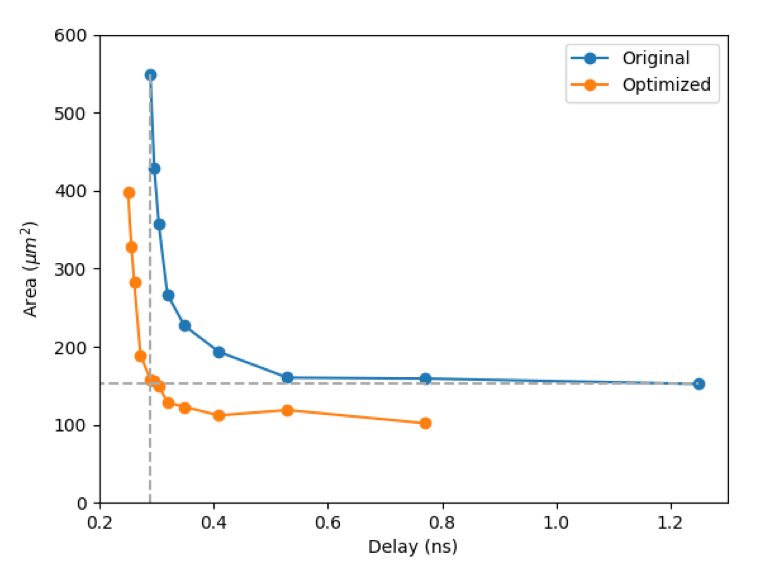

- NeuraLUT-Assemble: Hardware-aware Assembling of Sub-Neural Networks for Efficient LUT Inference, joint work between my PhD student Marta Andronic and me. I think this is a landmark paper in terms of the results that Marta has been able to achieve. Compared to her earlier NeuraLUT work which I’ve blogged on previously, she has added a way to break down large LUTs into trees of smaller LUTs, and a hardware-aware way to learn sparsity patterns that work best, localising nonlinear interactions in these neural networks to within lookup tables. The impact of these changes on the area and delay of her designs is truly impressive.

memory structures for soft processors

Overall, it was well worth attending. Next year, Callie will be hosting FCCM in Atlanta.