This blog collects some of my notes on classical computational learning theory, based on my reading of Kearns and Vazirani. The results are (almost) all from their book, the sloganising (and mistakes, no doubt) are mine.

The Probably Approximately Correct (PAC) Framework

Definition (Instance Space). An instance space is a set, typically denoted  . It is the set of objects we are trying to learn about.

. It is the set of objects we are trying to learn about.

Definition (Concept). A concept  over

over  is a subset of the instance space

is a subset of the instance space  .

.

Although not covered in Kearns and Vazirani, in general it is possible to generalise beyond Boolean membership to some degree of uncertainty or fuzziness – I hope to cover this in a future blog post.

Definition (Concept Class). A concept class  is a set of concepts, i.e.

is a set of concepts, i.e.  , where

, where  denotes power set. We will follow Kearns and Vazirani and also use

denotes power set. We will follow Kearns and Vazirani and also use  to denote the corresponding indicator function

to denote the corresponding indicator function  .

.

In PAC learning, we assume  is known, but the target class

is known, but the target class  is not. However, it doesn’t seem a jump to allow for unknown target class, in an appropriate approximation setting – I would welcome comments on established frameworks for this.

is not. However, it doesn’t seem a jump to allow for unknown target class, in an appropriate approximation setting – I would welcome comments on established frameworks for this.

Definition (Target Distribution). A target distribution  is a probability distribution over

is a probability distribution over  .

.

In PAC learning, we assume  is unknown.

is unknown.

Definition (Oracle). An oracle is a function  taking a concept class and a distribution, and returning a labelled example

taking a concept class and a distribution, and returning a labelled example  where

where  is drawn randomly and independently from

is drawn randomly and independently from  .

.

Definition (Error). The error of a hypothesis concept class  with reference to a target concept class

with reference to a target concept class  and target distribution

and target distribution  , is

, is  , where

, where  denotes probability.

denotes probability.

Definition (Representation Scheme). A representation scheme for a concept class  is a function

is a function  where

where  is a finite alphabet of symbols (or – following the Real RAM model – a finite alphabet augmented with real numbers).

is a finite alphabet of symbols (or – following the Real RAM model – a finite alphabet augmented with real numbers).

Definition (Representation Class). A representation class is a concept class together with a fixed representation scheme for that class.

Definition (Size). We associate a size  with each string from a representation alphabet

with each string from a representation alphabet  . We similarly associate a size with each concept

. We similarly associate a size with each concept  via the size of its minimal representation

via the size of its minimal representation  .

.

Definition (PAC Learnable). Let  and

and  be representation classes classes over

be representation classes classes over  , where

, where  . We say that concept class

. We say that concept class  is PAC learnable using hypothesis class

is PAC learnable using hypothesis class  if there exists an algorithm that, given access to an oracle, when learning any target concept

if there exists an algorithm that, given access to an oracle, when learning any target concept  over any distribution

over any distribution  on

on  , and for any given

, and for any given  and

and  , with probability at least

, with probability at least  , outputs a hypothesis

, outputs a hypothesis  with

with  .

.

Definition (Efficiently PAC Learnable). Let  and

and  be representation classes classes over

be representation classes classes over  , where

, where  for all

for all  . Let

. Let  or

or  . Let

. Let  ,

,  , and

, and  . We say that concept class

. We say that concept class  is efficiently PAC learnable using hypothesis class

is efficiently PAC learnable using hypothesis class  if there exists an algorithm that, given access to a constant time oracle, when learning any target concept

if there exists an algorithm that, given access to a constant time oracle, when learning any target concept  over any distribution

over any distribution  on

on  , and for any given

, and for any given  and

and  :

:

- Runs in time polynomial in

,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  , and

, and

- With probability at least

, outputs a hypothesis

, outputs a hypothesis  with

with  .

.

There is much of interest to unpick in these definitions. Firstly, notice that we have defined a family of classes parameterised by dimension  , allowing us to talk in terms of asymptotic behaviour as dimensionality increases. Secondly, note the key parameters of PAC learnability:

, allowing us to talk in terms of asymptotic behaviour as dimensionality increases. Secondly, note the key parameters of PAC learnability:  (the ‘probably’ bit) and

(the ‘probably’ bit) and  (the ‘approximate’ bit). The first of these captures the idea that we may get really unlucky with our calls to the oracle, and get misleading training data. The second captures the idea that we are not aiming for certainty in our final classification accuracy, some pre-defined tolerance is allowable. Thirdly, note the requirements of efficiency: polynomial scaling in dimension, in size of the concept (complex concepts can be harder to learn), in error rate (the more sloppy, the easier), and in probability of algorithm failure to find a suitable hypothesis (you need to pay for more certainty). Finally, and most intricately, notice the separation of concept class from hypothesis class. We require the hypothesis class to be at least as general, so the concept we’re trying to learn is actually one of the returnable hypotheses, but it can be strictly more general. This is to avoid the case where the restricted hypothesis classes are harder to learn; Kearns and Vazirani, following Pitt and Valiant, give the example of learning the concept class 3-DNF using the hypothesis class 3-DNF is intractable, yet learning the same concept class with the more general hypothesis class 3-CNF is efficiently PAC learnable.

(the ‘approximate’ bit). The first of these captures the idea that we may get really unlucky with our calls to the oracle, and get misleading training data. The second captures the idea that we are not aiming for certainty in our final classification accuracy, some pre-defined tolerance is allowable. Thirdly, note the requirements of efficiency: polynomial scaling in dimension, in size of the concept (complex concepts can be harder to learn), in error rate (the more sloppy, the easier), and in probability of algorithm failure to find a suitable hypothesis (you need to pay for more certainty). Finally, and most intricately, notice the separation of concept class from hypothesis class. We require the hypothesis class to be at least as general, so the concept we’re trying to learn is actually one of the returnable hypotheses, but it can be strictly more general. This is to avoid the case where the restricted hypothesis classes are harder to learn; Kearns and Vazirani, following Pitt and Valiant, give the example of learning the concept class 3-DNF using the hypothesis class 3-DNF is intractable, yet learning the same concept class with the more general hypothesis class 3-CNF is efficiently PAC learnable.

Occam’s Razor

Definition (Occam Algorithm). Let  and

and  be real constants. An algorithm is an

be real constants. An algorithm is an  -Occam algorithm for

-Occam algorithm for  using

using  if, on an input sample

if, on an input sample  of cardinality

of cardinality  labelled by membership in

labelled by membership in  , the algorithm outputs a hypothesis

, the algorithm outputs a hypothesis  such that:

such that:

is consistent with

is consistent with  , i.e. there is no misclassification on

, i.e. there is no misclassification on

Thus Occam algorithms produce succinct hypotheses consistent with data. Note that the size of the hypothesis is allowed to grow only mildly – if at all – with the size of the dataset (via  ). Note, however, that there is nothing in this definition that suggests predictive power on unseen samples.

). Note, however, that there is nothing in this definition that suggests predictive power on unseen samples.

Definition (Efficient Occam Algorithm). An  -Occam algorithm is efficient iff its running time is polynomial in

-Occam algorithm is efficient iff its running time is polynomial in  ,

,  , and

, and  .

.

Theorem (Occam’s Razor). Let  be an efficient

be an efficient  -Occam algorithm for

-Occam algorithm for  using

using  . Let

. Let  be the target distribution over

be the target distribution over  , let

, let  be the target concept,

be the target concept,  . Then there is a constant

. Then there is a constant  such that if

such that if  is given as input a random sample

is given as input a random sample  of

of  examples drawn from oracle

examples drawn from oracle  , where

, where  satisfies

satisfies  , then

, then  runs in time polynomial in

runs in time polynomial in  ,

,  ,

,  and

and  and, with probability at least

and, with probability at least  , the output

, the output  of

of  satisfies

satisfies  .

.

This is a technically dense presentation, but it’s a philosophically beautiful result. Let’s unpick it a bit, so its essence is not obscured by notation. In summary, simple rules that are consistent with prior observations have predictive power! The ‘simple’ part here comes from  , and the predictive power comes from the bound on

, and the predictive power comes from the bound on  . Of course, one needs sufficient observations (the complex lower bound on

. Of course, one needs sufficient observations (the complex lower bound on  ) for this to hold. Notice that as

) for this to hold. Notice that as  approaches 1, and so – by the definition of an Occam algorithm – we get close to being able to memorise our entire training set – we need an arbitrarily large training set (memorisation doesn’t generalise).

approaches 1, and so – by the definition of an Occam algorithm – we get close to being able to memorise our entire training set – we need an arbitrarily large training set (memorisation doesn’t generalise).

Vapnik-Chervonenkis (VC) Dimension

Definition (Behaviours). The set of behaviours on  that are realised by

that are realised by  , is defined by

, is defined by  .

.

Each of the points in  is either included in a given concept or not. Each tuple

is either included in a given concept or not. Each tuple  then forms a kind of fingerprint of

then forms a kind of fingerprint of  according to a particular concept. The set of behaviours is the set of all such fingerprints across the whole concept class..

according to a particular concept. The set of behaviours is the set of all such fingerprints across the whole concept class..

Definition (Shattered). A set  is shattered by

is shattered by  iff

iff  .

.

Note that  is the maximum cardinality that’s possible, i.e. the set of behaviours is all possible behaviours. So we can think of a set as being shattered by a concept class iff there’s no combination of inclusion/exclusion in the concepts that isn’t represented at least once in the set.

is the maximum cardinality that’s possible, i.e. the set of behaviours is all possible behaviours. So we can think of a set as being shattered by a concept class iff there’s no combination of inclusion/exclusion in the concepts that isn’t represented at least once in the set.

Definition (Vapnik-Chervonenkis Dimension). The VC dimension of  , denoted

, denoted  , is the cardinality of the largest set shattered by

, is the cardinality of the largest set shattered by  . If arbitrarily large finite sets can be shattered by

. If arbitrarily large finite sets can be shattered by  , then

, then  .

.

VC dimension in this sense captures the ability of  to discern between samples.

to discern between samples.

Theorem (PAC-learning in Low VC Dimension). Let  be any concept class. Let

be any concept class. Let  be any representation class off of VC dimension

be any representation class off of VC dimension  . Let

. Let  be any algorithm taking a set of

be any algorithm taking a set of  labelled examples of a concept

labelled examples of a concept  and producing a concept in

and producing a concept in  that is consistent with the examples. Then there exists a constant

that is consistent with the examples. Then there exists a constant  such that

such that  is a PAC learning algorithm for

is a PAC learning algorithm for  using

using  when it is given examples from

when it is given examples from  , and when

, and when  .

.

Let’s take a look at the similarity between this theorem and Occam’s razor, presented in the last section of this blog post. Both bounds have a similar feel, but the VCD-based bound does not depend on  ; indeed it’s possible that the size of hypotheses is infinite and yet the VCD is still finite.

; indeed it’s possible that the size of hypotheses is infinite and yet the VCD is still finite.

As the theorem below shows, the linear dependence on VCD achieved in the above theorem is actually the best one can do.

Theorem (PAC-learning Minimum Samples). Any algorithm for PAC-learning a concept class of VC dimension  must use

must use  examples in the worst case.

examples in the worst case.

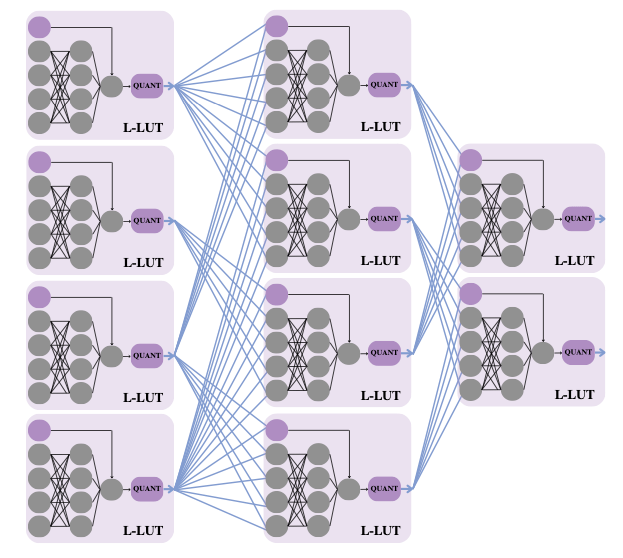

Definition (Layered DAG). A layered DAG is a DAG in which each vertex is associated with a layer  and in which the edges are always from some layer

and in which the edges are always from some layer  to the next layer

to the next layer  . Vertices at layer 0 have indegree 0 and are referred to as input nodes. Vertices at other layers are referred to as internal nodes. There is a single output node of outdegree 0.

. Vertices at layer 0 have indegree 0 and are referred to as input nodes. Vertices at other layers are referred to as internal nodes. There is a single output node of outdegree 0.

Definition ( -composition). For a layered DAG

-composition). For a layered DAG  and a concept class

and a concept class  , the G-composition of

, the G-composition of  is the class of all concepts that can be obtained by: (i) associating a concept

is the class of all concepts that can be obtained by: (i) associating a concept  with each vertex

with each vertex  in

in  , (ii) applying the concept at each node to its predecessor nodes.

, (ii) applying the concept at each node to its predecessor nodes.

Notice that this way we can think of the internal nodes as forming a Boolean circuit with a single output; the  -composition is the concept class we obtain by restricting concepts to only those computable with the structure

-composition is the concept class we obtain by restricting concepts to only those computable with the structure  . This is a very natural way of composing concepts – so what kind of VCD arises through this composition? This theorem provides an answer:

. This is a very natural way of composing concepts – so what kind of VCD arises through this composition? This theorem provides an answer:

Theorem (VCD Compositional Bound). Let  be a layered DAG with

be a layered DAG with  input nodes and

input nodes and  internal nodes, each of indegree

internal nodes, each of indegree  . Let

. Let  be a concept class over

be a concept class over  of VC dimension

of VC dimension  , and let

, and let  be the

be the  -composition of

-composition of  . Then

. Then  .

.

Weak PAC Learnability

Definition (Weak PAC Learning). Let  be a concept class and let

be a concept class and let  be an algorithm that is given access to

be an algorithm that is given access to  for target concept

for target concept  and distribution

and distribution  .

.  is a weak PAC learning algorithm for

is a weak PAC learning algorithm for  using

using  if there exist polynomials

if there exist polynomials  and

and  such that

such that  outputs a hypothesis

outputs a hypothesis  that with probability at least

that with probability at least  satisfies

satisfies  .

.

Kearns and Vazirani justifiably describe weak PAC learning as “the weakest demand we could place on an algorithm in the PAC setting without trivialising the problem”: if these were exponential rather than polynomial functions in  , the problem is trivial: take a fixed-size random sample of the concept and memorise it, randomly guess with probability 50% outside the memorised sample. The remarkable result is that efficient weak PAC learnability and efficient PAC learnability coincide for an appropriate PAC hypothesis class, based on ternary majority trees.

, the problem is trivial: take a fixed-size random sample of the concept and memorise it, randomly guess with probability 50% outside the memorised sample. The remarkable result is that efficient weak PAC learnability and efficient PAC learnability coincide for an appropriate PAC hypothesis class, based on ternary majority trees.

Definition (Ternary Majority Tree). A ternary majority tree with leaves from  is a tree where each non-leaf node computes a majority (voting) function of its three children, and each leaf is labelled with a hypothesis from

is a tree where each non-leaf node computes a majority (voting) function of its three children, and each leaf is labelled with a hypothesis from  .

.

Theorem (Weak PAC learnability is PAC learnability). Let  be any concept class and

be any concept class and  any hypothesis class. Then if

any hypothesis class. Then if  is efficiently weakly PAC learnable using

is efficiently weakly PAC learnable using  , it follows that

, it follows that  is efficiently PAC learnable using a hypothesis class of ternary majority trees with leaves from

is efficiently PAC learnable using a hypothesis class of ternary majority trees with leaves from  .

.

Kearns and Varzirani provide an algorithm to learn this way. The details are described in their book, but the basic principle is based on “boosting”, as developed in the lemma to follow.

Definition (Filtered Distributions). Given a distribution  and a hypothesis

and a hypothesis  we define

we define  to be the distribution obtained by flipping a fair coin and, on a heads, drawing from

to be the distribution obtained by flipping a fair coin and, on a heads, drawing from  until

until  agrees with the label; on a tails, drawing from

agrees with the label; on a tails, drawing from  until

until  disagrees with the label. Invoking a weak learning algorithm on data from this new distribution yields a new hypothesis

disagrees with the label. Invoking a weak learning algorithm on data from this new distribution yields a new hypothesis  . Similarly, we define

. Similarly, we define  to be the distribution obtained by drawing examples from

to be the distribution obtained by drawing examples from  until we find an example on which

until we find an example on which  and

and  disagree.

disagree.

What’s going on in these constructions is quite clever:  has been constructed so that it must contain new information about

has been constructed so that it must contain new information about  , compared to

, compared to  ;

;  has, by construction, no advantage over a coin flip on

has, by construction, no advantage over a coin flip on  . Similarly,

. Similarly,  contains new information about

contains new information about  not already contained in

not already contained in  and

and  , namely on the points where they disagree. Thus, one would expect that hypotheses that work in these three cases could be combined to give us a better overall hypothesis. This is indeed the case, as the following lemma shows.

, namely on the points where they disagree. Thus, one would expect that hypotheses that work in these three cases could be combined to give us a better overall hypothesis. This is indeed the case, as the following lemma shows.

Lemma (Boosting). Let  . Let the distributions

. Let the distributions  ,

,  ,

,  be defined above, and let

be defined above, and let  ,

,  and

and  satisfy

satisfy  ,

,  ,

,  . Then if

. Then if  , it follows that

, it follows that  .

.

The function  is monotone and strictly decreasing over

is monotone and strictly decreasing over  . Hence by combining three hypotheses with only marginally better accuracy than flipping a coin, the boosting lemma tells us that we can obtain a strictly stronger hypothesis. The algorithm for (strong) PAC learnability therefore involves recursively calling this boosting procedure, leading to the majority tree – based hypothesis class. Of course, one needs to show that the depth of the recursion is not too large and that we can sample from the filtered distributions with not too many calls to the overall oracle

. Hence by combining three hypotheses with only marginally better accuracy than flipping a coin, the boosting lemma tells us that we can obtain a strictly stronger hypothesis. The algorithm for (strong) PAC learnability therefore involves recursively calling this boosting procedure, leading to the majority tree – based hypothesis class. Of course, one needs to show that the depth of the recursion is not too large and that we can sample from the filtered distributions with not too many calls to the overall oracle  , so that the polynomial complexity bound in the PAC definition is maintained. Kearns and Vazirani include these two results in the book.

, so that the polynomial complexity bound in the PAC definition is maintained. Kearns and Vazirani include these two results in the book.

Learning from Noisy Data

Up until this point, we have only dealt with correctly classified training data. The introduction of a noisy oracle allows us to move beyond this limitation.

Definition (Noisy Oracle). A noisy oracle  extends the earlier idea of an oracle with an additional noise parameter

extends the earlier idea of an oracle with an additional noise parameter  . This oracle behaves in the identical way to

. This oracle behaves in the identical way to  except that it returns the wrong classification with probability

except that it returns the wrong classification with probability  .

.

Definition (PAC Learnable from Noisy Data). Let  be a concept class and let

be a concept class and let  be a representation class over

be a representation class over  . Then

. Then  is PAC learnable from noisy data using

is PAC learnable from noisy data using  if there exists and algorithm such that: for any concept

if there exists and algorithm such that: for any concept  , any distribution

, any distribution  on

on  , any

, any  , and any

, and any  ,

,  and

and  with

with  , given access to a noisy oracle

, given access to a noisy oracle  and inputs

and inputs  ,

,  ,

,  , with probability at least

, with probability at least  the algorithm outputs a hypothesis concept

the algorithm outputs a hypothesis concept  with

with  . If the runtime of the algorithm is polynomial in

. If the runtime of the algorithm is polynomial in  ,

,  ,

,  and

and  then

then  is efficiently learnable from noisy data using

is efficiently learnable from noisy data using  .

.

Let’s unpick this definition a bit. The main difference from the PAC definition is simply the addition of noise via the oracle and an additional parameter  which bounds the error of the oracle; thus the algorithm is allowed to know in advance an upper bound on the noisiness of the data, and an efficient algorithm is allowed to take more time on more noisy data.

which bounds the error of the oracle; thus the algorithm is allowed to know in advance an upper bound on the noisiness of the data, and an efficient algorithm is allowed to take more time on more noisy data.

Kearns and Vazirani address PAC learnability from noisy data in an indirect way, via the use of a slightly different framework, introduced below.

Definition (Statistical Oracle). A statistical oracle  takes queries of the form

takes queries of the form  where

where  and

and  , and returns a value

, and returns a value  satisfying

satisfying  where

where ![P_\chi = Pr_{x \in {\mathcal D}}[ \chi(x, c(x)) = 1 ]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=P_%5Cchi+%3D+Pr_%7Bx+%5Cin+%7B%5Cmathcal+D%7D%7D%5B+%5Cchi%28x%2C+c%28x%29%29+%3D+1+%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0&c=20201002) .

.

Definition (Learnable from Statistical Queries). Let  be a concept class and let

be a concept class and let  be a representation class over

be a representation class over  . Then

. Then  is efficiently learnable from statistical learning queries using

is efficiently learnable from statistical learning queries using  if there exists a learning algorithm

if there exists a learning algorithm  and polynomials

and polynomials  ,

,  and

and  such that: for any

such that: for any  , any distribution

, any distribution  over

over  and any

and any  , if given access to

, if given access to  , the following hold. (i) For every query

, the following hold. (i) For every query  made by

made by  , the predicate

, the predicate  can be evaluated in time

can be evaluated in time  , and

, and  , (ii)

, (ii)  has execution time bounded by

has execution time bounded by  , (iii)

, (iii)  outputs a hypothesis

outputs a hypothesis  that satisfies

that satisfies  .

.

So a statistical oracle can be asked about a whole predicate  , for any given tolerance

, for any given tolerance  . The oracle must return an estimate of the probability that this predicate holds (where the probability is over the distribution over

. The oracle must return an estimate of the probability that this predicate holds (where the probability is over the distribution over  ). It is, perhaps, not entirely obvious how to relate this back to the more obvious noisy oracle used above. However, it is worth noting that one can construct a statistical oracle that works with high probability by taking enough samples from a standard oracle, and then returning the relative frequency of

). It is, perhaps, not entirely obvious how to relate this back to the more obvious noisy oracle used above. However, it is worth noting that one can construct a statistical oracle that works with high probability by taking enough samples from a standard oracle, and then returning the relative frequency of  evaluating to 1 on that sample. Kearns and Vazirani provide an intricate construction to efficiently sample from a noisy oracle to produce a statistical oracle with high probability. In essence, this then allows an algorithm that can learn from statistical queries to be used to learn from noisy data, resulting in the following theorem.

evaluating to 1 on that sample. Kearns and Vazirani provide an intricate construction to efficiently sample from a noisy oracle to produce a statistical oracle with high probability. In essence, this then allows an algorithm that can learn from statistical queries to be used to learn from noisy data, resulting in the following theorem.

Theorem (Learnable from Statistical Queries means Learnable from Noisy Data). Let  be a concept class and let

be a concept class and let  be a representation class over

be a representation class over  . Then if

. Then if  is efficiently learnable from statistical queries using

is efficiently learnable from statistical queries using  ,

,  is also efficiently PAC learnable using

is also efficiently PAC learnable using  in the presence of classification noise.

in the presence of classification noise.

Hardness Results

I mentioned earlier in this post that Pitt and Valiant showed that sometimes we want more general hypothesis classes than concept classes: the concept class 3-DNF using the hypothesis class 3-DNF is intractable, yet learning the same concept class with the more general hypothesis class 3-CNF is efficiently PAC learnable. So in their chapter Inherent Unpredictability, Kearns and Vazirani turn their attention to the case where a concept class is hard to learn independent of the choice of a hypothesis class. This leads to some quite profound results for those of us interested in Boolean circuits.

We will need some kind of hardness assumption to develop hardness results for learning. In particular, note that if  , then by Occam’s Razor (above) polynomially evaluable hypothesis classes are also polynomially-learnable ones. So we will need to do two things: focus our attention on polynomially evaluable hypothesis classes (or we can’t hope to learn them polynomially), and make a suitable hardness assumption. The latter requires a very brief detour into some results commonly associated with cryptography.

, then by Occam’s Razor (above) polynomially evaluable hypothesis classes are also polynomially-learnable ones. So we will need to do two things: focus our attention on polynomially evaluable hypothesis classes (or we can’t hope to learn them polynomially), and make a suitable hardness assumption. The latter requires a very brief detour into some results commonly associated with cryptography.

Let  . We define the cubing function

. We define the cubing function  by

by  . Let

. Let  define Euler’s totient function. Then if

define Euler’s totient function. Then if  is not a multiple of three, it turns out that

is not a multiple of three, it turns out that  is bijective, so we can talk of a unique discrete cube root.

is bijective, so we can talk of a unique discrete cube root.

Definition (Discrete Cube Root Problem). Let  and

and  be two

be two  -bit primes with

-bit primes with  not a multiple of 3, where

not a multiple of 3, where  . Given

. Given  and

and  as input, output

as input, output  .

.

Definition (Discrete Cube Root Assumption). For every polynomial  , there is no algorithm that runs in time

, there is no algorithm that runs in time  that solves the discrete cube root problem with probability at least

that solves the discrete cube root problem with probability at least  , where the probability is taken over randomisation of

, where the probability is taken over randomisation of  ,

,  ,

,  and any internal randomisation of the algorithm

and any internal randomisation of the algorithm  . (Where

. (Where  ).

).

This Discrete Cube Root Assumption is widely known and studied, and forms the basis of the learning complexity results presented by Kearns and Vazirani.

Theorem (Concepts Computed by Small, Shallow Boolean Circuits are Hard to Learn). Under the Discrete Cube Root Assumption, the representation class of polynomial-size, log-depth Boolean circuits is not efficiently PAC learnable (using any polynomially evaluable hypothesis class).

The result also holds if one removes the log-depth requirement, but this result shows that even by restricting ourselves to only log-depth circuits, hardness remains.

In case any of my blog readers knows: please contact me directly if you’re aware of any resource of positive results on learnability of any compositionally closed non-trivial restricted classes of Boolean circuits.

The construction used to provide the result above for Boolean circuits can be generalised to neural networks:

Theorem (Concepts Computed by Neural Networks are Hard to Learn). Under the Discrete Cube Root Assumption, there is a polynomial  and an infinite family of directed acyclic graphs (neural network architectures)

and an infinite family of directed acyclic graphs (neural network architectures)  such that each

such that each  has

has  Boolean inputs and at most

Boolean inputs and at most  nodes, the depth of

nodes, the depth of  is a constant independent of

is a constant independent of  , but the representation class

, but the representation class  is not efficiently PAC learnable (using any polynomially evaluable hypothesis class), and even if the weights are restricted to be binary.

is not efficiently PAC learnable (using any polynomially evaluable hypothesis class), and even if the weights are restricted to be binary.

Through an appropriate natural definition of reduction in PAC learning, Kearns and Vazirani show that the PAC-learnability of all these classes reduce to functions computed by deterministic finite automata. So, in particular:

Theorem (Concepts Computed by Deterministic Finite Automata are Hard to Learn). Under the Discrete Cube Root Assumption, the representation class of Deterministic Finite Automata is not efficiently PAC learnable (using any polynomially evaluable hypothesis class).

It is this result that motivates the final chapter of the book.

Experimentation in Learning

As discussed above, PAC model utilises an oracle that returns labelled samples  . An interesting question is whether more learning power arises if we allow the algorithms to be able to select

. An interesting question is whether more learning power arises if we allow the algorithms to be able to select  themselves, with the oracle returning

themselves, with the oracle returning  , i.e. not just to be shown randomly selected examples but take charge and test their understanding of the concept.

, i.e. not just to be shown randomly selected examples but take charge and test their understanding of the concept.

Definition (Membership Query). A membership query oracle takes any instance  and returns its classification

and returns its classification  .

.

Definition (Equivalence Query). An equivalence query oracle takes a hypothesis concept  and determines whether there is an instance

and determines whether there is an instance  on which

on which  , returning this counterexample if so.

, returning this counterexample if so.

Definition (Learnable From Membership and Equivalence Queries). The representation class  is efficiently exactly learnable from membership and equivalence queries if there is a polynomial

is efficiently exactly learnable from membership and equivalence queries if there is a polynomial  and an algorithm with access to membership and equivalence oracles such that for any target concept

and an algorithm with access to membership and equivalence oracles such that for any target concept  , the algorithm outputs the concept

, the algorithm outputs the concept  in time

in time  .

.

There are a couple of things to note about this definition. It appears to be a much stronger requirement than PAC learning, as the concept must be exactly learnt. On the other hand, the existence of these more sophisticated oracles, especially the equivalence query oracle, appears to narrow the scope. Kearns and Vazirani encourage the reader to prove that the true strengthening over PAC-learnability is in the membership queries:

Theorem (Exact Learnability from Membership and Equivalence means PAC-learnable with only Membership). For any representation class  , if

, if  is efficiently exactly learnable from membership and equivalence queries, then

is efficiently exactly learnable from membership and equivalence queries, then  is also efficiently learnable in the PAC model with membership queries.

is also efficiently learnable in the PAC model with membership queries.

They then provide an explicit algorithm, based on these two new oracles, to efficiently exactly learn deterministic finite automata.

Theorem (Experiments Make Deterministic Finite Automata Efficiently Learnable). The representation class of Deterministic Finite Automata is efficiently exactly learnable from membership and equivalence queries.

Note the contrast with the hardness result of the previous section: through the addition of experimentation, we have gone from infeasible learnability to efficient learnability. Another very philosophically pleasing result.

whose coordinates are partitioned into blocks

.

is a vector of low-precision mantissas, and

is a scalar shared scaling factor.

need not be normalized, and in many formats their entries may have quite different magnitudes (for example in integer mantissa formats such as MXINT). However this does not change the geometry. The representation

is invariant to rescaling of

: multiplying

by any constant simply rescales

by the inverse factor. What matters for the approximation is therefore only the direction of

, i.e. the one-dimensional subspace it spans.

of a vector into its magnitude and direction, but applied locally within blocks.

points roughly in the same direction as the original block

, then scaling it appropriately produces a good approximation of that block.

is not chosen arbitrarily, but rather is the best possible scale for that block in the least squares sense, for whatever mantissa vector we choose, i.e.

. Then

is the orthogonal projection of

onto the line spanned by

.

.

.

, which we can think of as the fraction of the vector’s energy contained in block

; these add to 1 over the whole vector. Now we can state the result:

.

represent how much of the vector’s energy lies in each block. Blocks that contain very little energy contribute very little to the final direction. The important consequence is that direction errors do not accumulate catastrophically across blocks. Instead, the overall directional error simply depends on a weighted average of the block direction errors. In other words, if block number formats preserve the directions of individual blocks, they automatically preserve the direction of the entire vector.

, the approximation

with

chosen by least squares is the orthogonal projection of

onto the line spanned by

.

where

is orthogonal to

.

gives

.

.

.

.

, we obtain

.

.

.

, and writing

,

.

, we obtain

.