Designing circuits is not easy. Mistakes can be made, and mistakes made are not easily fixed. Even leaving aside safety-critical applications, product recalls can cost upwards of hundreds of millions of US$, and nobody wants to be responsible for that. As a result, the industry invests a huge effort in formally verifying hardware designs, that is coming up with computer-generated or computer-assisted proofs of hardware correctness.

My Intel-funded PhD student Sam Coward (jointly advised by Theo Drane) is about to head off to FMCAD 2023 in Ames, Iowa, to present a contribution to making this proof generation process speedier and more automated, while still relying on industry-standard tried and trusted formal verification tools. Together with his Intel colleague Emiliano Morini and then-intern (and Imperial student) Bryan Tan, Sam noticed that the e-graph techniques we have been using in his PhD for optimising datapath [1, 2] also have a natural application to verifying datapath designs, akin – but distinct – to their long-time use as a data-structure in SMT solvers.

The basic idea is straight-forward. Ever since our earliest ARITH paper, we’ve developed a toolbox of Intel-inspired rewrite rules that can be applied to optimise designs across parametric bitwidths. Our optimisation flow, called ROVER, applies these to a single expression we wish to optimise, and then we extract a minimal cost implementation. Our new paper asks a different question: what if we start, not from a single expression we wish to optimise, but from two expressions we’re trying to prove to be equivalent?

Following the approach I blogged about here from ROVER, if the expressions are not equivalent then they should never end up in the same equivalence class after multiple rewrite iterations. If they are equivalent then they may or may not end up in the same equivalence class: we provide no guarantees of completeness. So let’s think about what happens in each of these cases.

If they end up in the same equivalence class, then our tool thinks it has proven the two expressions to be equivalent. But no industrial design team will trust our tool to just say so – and rightly so! – tool writers make mistakes too. However, work by Sam and other colleagues from the Universities of Washington and Utah, has provided a methodology by which we can use our tool’s reasoning to export hints, in the form of intermediate proof steps, to a trusted industrial formal verification tool. And so this is how we proceed: our tool will generate many, sometimes hundreds, of hints which will help state-of-the-art industrial formal verification tools to find proofs more quickly – sometimes much more quickly – than they were able to do so beforehand.

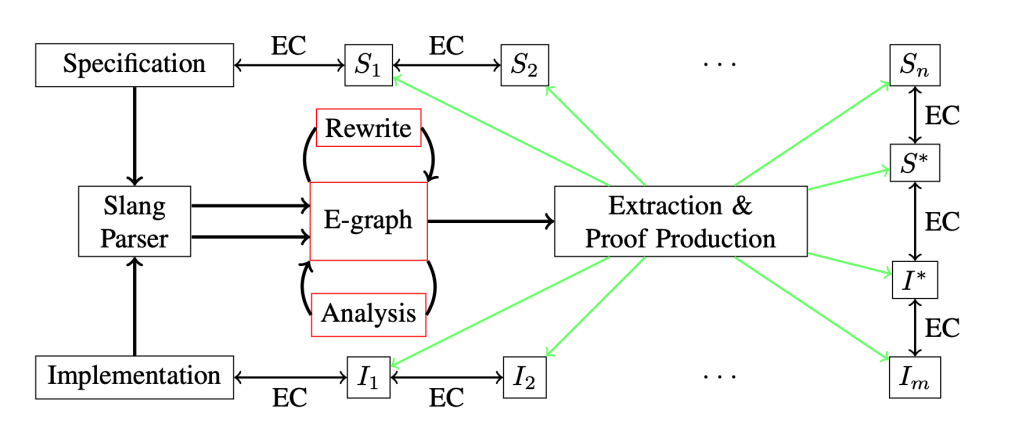

So what if the two expressions don’t end up in the same equivalence class, despite actually being equivalent? No problem! We can still find two expressions for which their proof of equivalence, via some external tool, makes the overall proof we’re aiming for much easier… crunching down the proof to its hard essence, stripping away what we can. The main technical idea here is how to extract the expressions from the e-graph. Rather than aiming for the best possible implementation cost, as we did with ROVER, we aim to minimise the distance between the two implementations that are left for the industrial tool to verify. The overall process is shown in the figure below, where “EC” refers to an equivalence check conducted by the industrially-trusted tool and and

are the extracted “close” expressions.

We show one example where, without the hints provided by our tool, the industrial formal verifier does not complete within a 24 hour timeout. Even when results are achievable with the industrial formal verifier, we still get an up to a 6x speedup in proof convergence.

This work forms a really nice “power use” of e-graphs. If you are at FMCAD 2023, come along and hear Sam talk about it in person!

One thought on “Supercharging Formal with E-Graphs”