My PhD student Sam Coward (jointly advised by Theo Drane from Intel) is about to head off on a speaking tour, where he will be explaining some of our really exciting recent developments. We’ve developed an approach that allows the discovery, exploitation, and generation of datapath hardware that works well in certain special cases. We’ve developed some theory (based on abstract interpretation), some software (based on egg), and some applications (notably in floating-point hardware design). Sam will be formally presenting this work at SOAP, EGRAPHS, and DAC over the coming weeks. In this blog post, I will try to explain the essence of the work. More detail can be found in the papers, primarily [1,2], with [3] for background.

We know that sometimes we can take shortcuts in computation. As a trivial example, we know that can just be replaced by

for non-negative values of

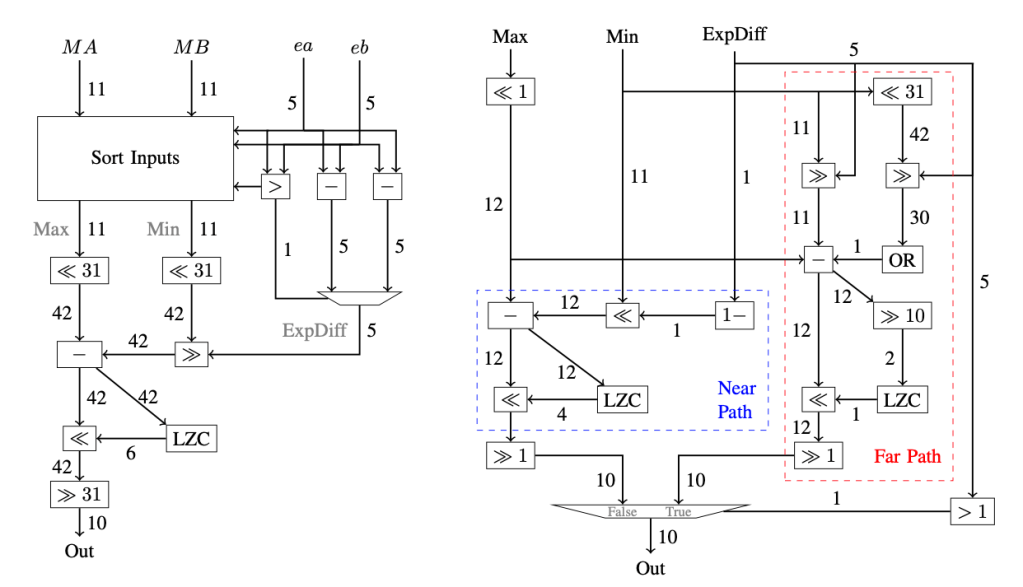

. Special cases abound, and are often used in complex ways to create really efficient hardware. A great example of this is the near/far-path floating-point adder. Since the publication of this idea by Oberman and Flynn in the late 1990s, designs based on this have become standard in modern hardware. These designs use the observation that there are two useful distinct regimes to consider when adding two values of differing sign. If the numbers are close in magnitude then very little work has to be done to align their mantissas, yet a lot of work might be required to renormalise the result of the addition. On the other hand, if the two numbers are far in magnitude then a lot of work might be needed to align their mantissas, yet very little is required to renormalise the result of the addition. Thus we never see both alignment and renormalisation being significant computational steps.

Readers of this blog may remember that Sam, Theo and I published a paper at ARITH 2022 that demonstrated that e-graphs can be used to discover hardware that is equivalent in functionality, but better in power, performance, and area. E-graphs are built by repeatedly using rewrite rules of the form , e.g.

. But our original ARITH paper wasn’t able to consider special cases. What we really need for that is some kind of conditional rewrite rules, e.g.

, where I am using math script to denote the value of a variable and teletype script to denote an expression.

So we set out to answer:

- how can we deal with conditional rewrites in our e-graphs?

- how can we evaluate whether a condition is true in a certain context?

- how can we make use of this to discover and optimise special cases in numerical hardware?

Based on an initial suggestion from Pavel Panchekha, Sam developed an approach to conditionality by imagining augmenting the domain in which we’re working with an additional element, let’s call it . Now let’s imagine introducing a new operator

that takes two expressions, the second of which is interpreted as a Boolean. Let’s give

the following semantics:

. In this way we can ‘lift’ equivalences in a subdomain to equivalences across the whole domain, and use e-graphs without modification to reason about these equivalences. Taking the absolute value example from previously, we can write this equivalence as

. These

function symbols then appear directly within the e-graph data structure. Note that the assume on the right-hand side here is important: we need both sides of the rewrite to evaluate to the same value for all possible values of

, and they do: for negative values they both evaluate to

and for non-negative values they both evaluate to

.

So how do we actually evaluate whether a condition is true in a given context? This is essentially a program analysis question. Here we make use of a variation of classical interval arithmetic. However, traditionally interval arithmetic has been a fairly weak program analysis method. As an example, if we know that , then a classical evaluation of

would give me

, due to the loss of information about the correlation between the left and right-hand sides of the subtraction operator. Once again, our e-graph setting comes to the rescue! Taking this example, a rewrite

would likely fire, resulting in zero residing in the same e-class as

. Since the interval associated with

is

, the same interval will automatically be associated with

by our software, leading to a much more precise analysis.

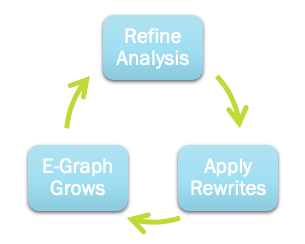

This interaction between rewrites and conditions goes even further: a more precise analysis leads to the possibility to fire more conditional rewrite rules, as more conditions will be known to hold; firing more rewrite rules results in an even more precise analysis. The two techniques reinforce each other in a virtuous cycle:

Our technique is able to discover, and generate RTL for, near/far-path floating-point adders from a naive RTL implementation (left transformed to right, below), resulting in a 33% performance advantage for the hardware.

I’m really excited by what Sam’s been able to achieve, as I really think that this kind of approach has the potential to lead to huge leaps forward in electronic design automation for word-level designs.

3 thoughts on “Discovering Special Cases”