Today was the 10th session of our math circle, and the first session I’ve led without the support of my wife. I had asked the school headteacher whether he could attend, so I was not alone faced with five children, and he thankfully agreed!

Today we explored three dimensional geometry. Over the Easter break, I’ve been reading a book by Kaplan and Kaplan on their experiences with their math circles (review to come in a future blog post), and this inspired me to try something different. We would spend a considerable time on definitions (which are the heart of mathematics, and often lost in trying to make mathematics appeal to primary school pupils) but these would – often – be definitions that the children themselves came up with through discussion and refinement. I was pleasantly surprised that even the “jumpiest” math circle members seemed to be OK with this approach, and contributed to the process of forming definitions.

We started by looking at 2D shapes. I drew some polygons on the board and one curvy shape and asked what the general name for the polygons was, expecting one of the older children to suggest the name “polygon”. However, this was not forthcoming. So we began discussing the differences between the shapes. Here we hit the second unexpected perspective: one of the children – rather creatively – suggested that “every” 2D shape is a polygon, because if you zoom in enough then the boundary becomes straight. We thus took a brief informal detour into limits, and ended up by concluding that this child had made a great contribution by ensuring “straight” and “finite” ended up in any definition they came up with. Since they were unsure what these shapes were called, following Kaplan and Kaplan, I suggested they find a name for them, and they settled on line-shape. Their final definition was: a line-shape is any shape made by a finite number of straight lines.

During the discussion on naming, two of the younger children suggested the word regular for those 2D shapes made from straight line segments. The older children disagreed, because they had seen regular polygons before, and instead insisted that a regular shape is a shape where the sides have the same length. (Nobody mentioned angles.)

Extending to 3D shapes, the children also did not naturally suggest the word “polyhedron“, however I was very impressed by the reasoning of one child, who suggested the term line-shape-shape “because if line-shapes are 2D shapes made of lines, then line-shape-shapes should be 3D shapes made of line-shapes!” After exploring these definitions a little more, I revealed the names polygon and polyhedron, and suggested we use them to avoid my own confusion!

I then had children make polyhedra using Polydron. As expected, they made a wide variety of weird and wonderful polyhedra. The oldest child had seen a (regular) icosahedron before and wanted to build one, but was trying to do so by constructing its net blind, unsuccessfully. All the polyhedra they constructed were convex, so I built a non-convex polyhedron and asked the children what made it different. They all agreed that it was because it “went in”, but I challenged them to figure out how they would convince someone else that this polyhedron “went in”. Eventually, I took a pencil and placed it on the polyhedron, at which one of the children noticed that there is a part of the pencil between the two touching points which is not itself part of the polyhedron. Thus we came to an agreed understanding of convexity.

These definitions were sufficient for me to (incorrectly at first!) define a Platonic solid as a convex polyhedron whose faces are regular polygons of the same shape and size.

I asked children to construct as many Platonic solids as possible, and they quickly came up with a tetrahedron and a cube. One child also came up with a decahedron consisting of two pentagonal-base pyramids joined, at which point I realised I had forgotten to include “and with the same number of faces meeting at each vertex” in my definition of a Platonic solid!

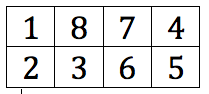

I introduced the children to Schläfli symbols {n,m} for a Platonic solid with m n-gon faces meeting at each vertex, and asked them to explore other Platonic solids. One child quickly discovered that hexagons cannot form the faces of a Platonic solid (because they tessellate three around a vertex, tiling the plane – in the words of the child “because of the angles”), but just moved onto another search rather than highlighting this important negative result; luckily I spotted it and queried him!

The school headteacher found {3,4}, the octahedron (identified immediately as ‘the shape of a d8’, i.e. an 8-sided die, by one of the children). The child who had previously tried to construct the icosahedron found that {3,6} does not exist, and therefore conjectured that {3,5} would be the missing icosahedron, which it was, much to her delight. The Schläfli symbol provided the extra information to enable her to make it, and she asked for permission to take a photo of it at the end “to show my dad!”

I was hoping to get to a proof that there are exactly five Platonic solids, but I will postpone this for next time, I think. And in the mean time, I will produce a worksheet summarising the definitions and results from this session.