This week my PhD student Marta Andronic will present our paper “PolyLUT: Learning Piecewise Polynomials for Ultra-Low Latency FPGA LUT-based Inference” at the International Conference on Field Programmable Technology (FPT), in Yokohama, Japan, where it has been short-listed for the best paper prize. In this blog post I hope to provide an accessible introduction to this exciting work.

FPGAs are a great platform for high-performance (and predictable performance) neural network inference. There’s a huge amount of work that’s gone into both the architecture of these devices and into the development of really high quality logic synthesis tools. In our work we look afresh at the question of how to best leverage both of these in order to do really low-latency inference, inspired by the use of neural networks in environments like CERN, where the speed of particle physics experiments and the volume of data generated demands really fast classification decisions: “is this an interesting particle interaction we’ve just observed?”

Our colleagues at Xilinx Research Labs (now part of AMD) published a great paper called LogicNets in 2020 that aimed to pack the combination of linear computation and activation function in a neural network into lookup tables in Verilog, a hardware description language, which then get implemented using the logic synthesis tools on the underlying soft-logic of the FPGA. Let’s be a bit more precise. The operation of a typical neuron in an artificial neural network is to compute the real-valued function for its inputs

and some learned weight vector

and bias

, where

is typically a fixed nonlinear function such as a ReLU. In practice, of course we use finite precision approximations to

and

. The Xilinx team noted that if they restrict the length of the vector

to be small enough, then the quantised version of this entire function can be implemented by simply enumerating all possible values of the input vector

to form a truth table for

, and using the back-end logic synthesis tools to implement this function efficiently, stitching together the neurons constructed in this way to form a hardware neural network. Moreover, note that in this setting one does not need to quantise the weights and bias at all – since the computation is absorbed in a truth table, arbitrary real-valued weights are just fine.

Marta and I have generalised this approach considerably. Firstly, we note that once we’re down at the level of enumerating truth tables, there’s no particular reason to limit ourselves to functions of the form – why not use an arbitrary function instead? From the perspective of the enumeration process and logic synthesis, it makes no difference. But from the perspective of neural network training, it certainly does. If we really wanted to look at arbitrary functions, we’d need a number of parameters to train that scales exponentially with the number of bits used to represent the entire vector

. This might be OK for very small vectors – indeed, with my former student Erwei Wang, I looked at something similar for the tiny physical lookup tables inside FPGA devices – but at the scale of neurons this is infeasible. So what family of functions should we use? Marta and I propose to use polynomials, where the total degree is fixed as a user-defined parameter we call

. In this way, we can tune a knob: turn down to

for minimal expressivity but the smallest number of parameters to train, and recover LogicNets as a special case; turn up

and you get much more expressive functions you can pack into your LUTs, at the cost of more parameters to train. In a classical neural network, composition of linear layers and ReLU functions gives rise to the overall computation of a continuous piecewise linear function. In our networks, we have continuous piecewise polynomial functions. The important thing, though, is that we never have to do all the expensive multiplications and additions one typically associates with evaluating a polynomial – the implementation is all just a table lookup for each neuron, just like in the linear case.

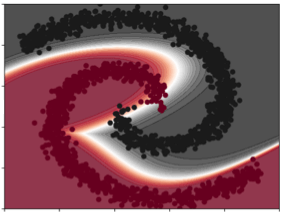

So what does higher degree actually buy us? It’s well known that deep neural networks of the classical form are universal function approximators, so with enough neurons (enough depth or width), we can arbitrarily closely approximate a continuous function anyway. But by packing in more functionality into each neuron, which anyway gets enumerated and implemented using lookup tables in the FPGA (just like the classical case), we can get the same accuracy with fewer layers of network. And fewer layers of network means fewer layers of Boolean logic, which means lower latency. In fact, we show in our results that one can often at least halve the latency by using our approach: we run 2x as fast! This two-fold speedup comes from the more intricate decision boundaries one can implement with polynomial compute; look at this beautiful near-separation of the two dot colours using a curved boundary, and imagine how many small linear segments you would need to do a similar job – this provides the intuition for just why our networks perform so well.

PolyLUT is available for others to use and experiment with. Don’t just take our word for it, download Marta’s code and try it out for yourself! I’m also delighted that Marta’s paper at FPT is one of just three at the conference to have earned all available ACM badges, verifying that not only is her work public, but it has been independently verified as reproducible. Thank you to the artifact review team for their work on the verification!